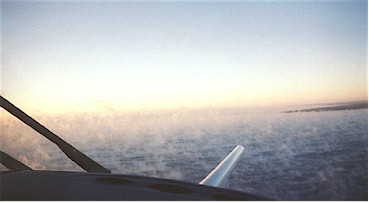

Weather forecasters can predict an upcoming lake-effect snowstorm, but the intensity of the storm, which communities will be hit, how far inland the snow will extend, and how long it will last are much harder to foresee. Like storm chasers hoping to solve weather mysteries, Illinois State Water Survey Head of the Center for Atmospheric Science David Kristovich, students, and colleagues have flown over the Great Lakes inside developing storms to study lake effects on winter storms in lakeside communities.

They have found snow present in the atmosphere even before the lake-effect cloud deck appears.

"Lake-effect snow usually occurs when skies are clear upwind of lakes, and a cloud deck forms over the lakes," Kristovich said. "We have found that transient puffs of clouds can leave bits of snow behind, preconditioning the atmosphere for heavier snowfall. This may be one reason why snow develops so quickly in lake-effect clouds over large lakes. In comparison, wintertime skies may be cloudy for hours before snow begins to fall."

Lake-effect snow develops when frigid air blows over warmer lakes, according to Kristovich.

"It's like turning on a stove," he said. "The sudden burst of heat under the cold air causes upward motions causing moisture from the lakes to condense into clouds. Some fraction of that moisture eventually falls back to the surface as snow."

These types of storms can be very intense, with the potential for dropping several feet of snow. Weather radar has even shown mini-cyclones dropping several inches of snow per hour in a small, localized area. By understanding surface water/atmosphere interactions, scientists can assist forecasters in providing more accurate warnings about the intensity of upcoming storms.

The amount of ice covering the lake also plays a role in winter weather. Although it would seem that an ice-covered lake would slow down the warming effect between air above and surface water below, lake-effect snow can still develop. Of course, some of the larger lakes, such as Lake Michigan, never completely freeze over.

In a recent field project, Kristovich used aircraft, flying just 50 yards over Lake Erie to measure the amount of moisture rising from the lake's surface. "Our most surprising finding was that even when the lake was 70 percent ice covered, the atmosphere almost acted as though the lake was completely thawed in that much more heat and moisture rose compared with a solid ice-covered lake," Kristovich said. "This may be why we still are occasionally surprised by lake-effect snowstorms when the lake is covered with ice."

Kristovich's future projects will focus on how climate change influences lake-effect snow. Meteorologists agree that the amount of lake-effect snow is increasing, but the reason is unknown.

The answer may be that the lakes are becoming warmer due to global warming, or that subtle changes in wind direction influence lake-effect snow, Kristovich said.

Despite the many unanswered questions about lake-effect snow, forecast models have improved tremendously in the past few decades.

"Not too many years ago, lakes were not even represented in global weather models," Kristovich said. "It's an important issue for forecasters. But to really understand the process, it requires multidisciplinary study within the field of meteorology. Scientifically, we're dealing with some very complicated issues."