Recently, my husband momentarily misplaced his wedding ring. While this might seem to be a commonplace, yet anxiety-inducing event, it created a unique moment of mnemonic crisis for us: my husband’s wedding band originally belonged to my grandfather, a metallurgist who forged the ring himself and engraved it with my grandmother’s initials and their wedding date in 1936, shortly after they fled Germany. As we searched for the ring we tried to remember what the engraving read; despite studying the words for years, we could not remember the exact arrangement of initials and dates. We wondered how we could replace the ring, its engraving, as well as its scratches and dents, the evidence it bore of the lives of generations of wearers. We found the ring, but the anxiety of loss lingers, urging me to reexamine my own relationship to the indexicality and transmission of generational memory and weigh what those of us in the second and third generation removed from trauma owe to our ancestors and to the past.

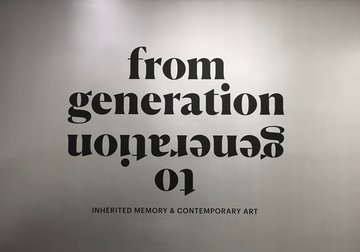

This personal meditation on generational memory actually began several weeks ago when I visited the exhibit “From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memories and Contemporary Art” at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. According to the curators, the title embraces “l’dor vador—the call to pass tradition from one generation to another,”[1] fitting the museum’s focus on representing contemporary Jewish culture. The exhibition employs Marianne Hirsch’s foundational concept of “postmemory” to thematically organize pieces from twenty-three international artists as they depict memories they have not experienced, but inherited. According to Hirsch, “postmemory describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma or transformation of those who came before—to events that they ‘remember’ only by means of stories, images and behaviors among which they grew up. But these events were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.”[2] The exhibit thus asks us to consider how various familial and cultural pasts are transmitted to these artists and how they choose to represent, as Hirsch describes, these “belated, temporally, and qualitatively removed” memories.

This personal meditation on generational memory actually began several weeks ago when I visited the exhibit “From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memories and Contemporary Art” at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. According to the curators, the title embraces “l’dor vador—the call to pass tradition from one generation to another,”[1] fitting the museum’s focus on representing contemporary Jewish culture. The exhibition employs Marianne Hirsch’s foundational concept of “postmemory” to thematically organize pieces from twenty-three international artists as they depict memories they have not experienced, but inherited. According to Hirsch, “postmemory describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma or transformation of those who came before—to events that they ‘remember’ only by means of stories, images and behaviors among which they grew up. But these events were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.”[2] The exhibit thus asks us to consider how various familial and cultural pasts are transmitted to these artists and how they choose to represent, as Hirsch describes, these “belated, temporally, and qualitatively removed” memories.

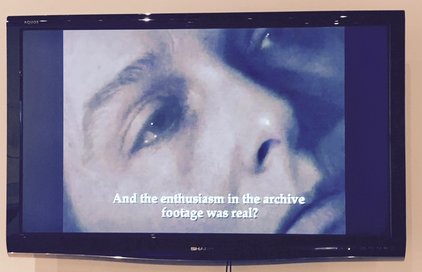

Despite this generational focus, only some of the works are primarily concerned with familial memories, those passed down from parents to children through not only overt methods such as storytelling and photographs, but also more subtle silences and affects. One of the pieces that specifically focuses on parental transmission is

Anri Sala’s Intervista (Finding the Words) (1998), where the artist attempts to reconstruct the lost vocal track of his mother’s speech to Albania’s Communist Youth Alliance, a recreation that his mother cannot recognize or remember almost thirty years later. Other than these intimate family portraits, most of the exhibit is concerned with larger cultural forces that shape generational memory, even within the family. This is not at odds with postmemory, as Hirsch argues, “Family life, even in its most intimate moments, is imbricated in a collective imaginary shaped by a shared archive of stories and images, by public fantasies and projections,” mediations that become especially important after traumatic events that resist comprehension and need multiple forms of repetition to work through, especially amongst families who do not speak openly about such pasts. Though trauma and transformation are often presented as breaks in the continuum between past and present, the “post” in “postmemory,” Hirsch writes, “reflects an uneasy oscillation between continuity and rupture,” where the past and present exist in uneasy yet entangled tension. Art is thus a valuable medium for working through difficult and transformative pasts while navigating the familial and the cultural, the personal and the collective, to see how the past resonates today, shaping our hopes for the future.

Anri Sala’s "Intervista" (1998)

The exhibition is loosely broken up into three parts: personal, collective, and future memories, although these scales are often blurred. In “personal memories,” intimate and often painful moments in the lives of individuals are represented, encouraging us to consider not only the artists’ relationship to their subjects, but ours as well. In

Amelia Falling (2014), artist Hank Willis Thomas prints a photograph of Civil Rights activist

Amelia Boynton after she was beaten unconscious in the Selma, Alabama march of 1965 by State Troopers on a reflective mirror.

[3] Thomas focuses on Boynton in mid-faint as she is supported by two marchers, allowing viewers to see themselves reflected above the distressed trio. Placing the viewer in this event collapses the distinction between the personal and the collective, the past and present, asking us to empathize with Boynton’s personal suffering while connecting this difficult historical moment to current instances of police brutality.

Reflected in "Amelia Falling" (2014)

In a similar act of intimate mediation of inter-generational transmission, Nao Bustamante’s installation Chac-Mool (2015) transmits the memories of Leandra Becerra Lumbreras, who at a purported 127 years old, was the last surviving soldadera, or female fighter in the Mexican Revolution. Sitting on a stool in front of a makeshift wooden video player, we are invited to peer into a viewfinder and listen on headphones to Lumbreras beat out a revolutionary anthem on her drum. Thus the originary intimate process of intergenerational memory transfer between the artist and her subject is replicated through Chac-Mool, where the personal stories and defiant affect of Lumbreras are passed on to us, the museum visitors. The endurance of Lumbreras’s tune is reiterated in Bustamante’s other piece, Kevlar Fighting Costumes (2015), where the signature dresses of the soldaderas are reproduced in bullet-proof Kevlar. This retroactive effort to protect the female soldaderas is also an attempt to preserve their legacy and empower new generations of feminists and female freedom fighters.

Detail from "Chac-Mool" (2015)

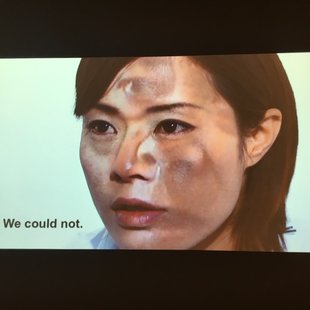

This theme of testimony eliciting intergenerational empathetic attachment is reiterated in Chickako Yamashiro’s powerful video, Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat (2009), where a survivor of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 tells his story through the mouth of the young artist. As his voice speaks through her moving lips, the artist begins to cry in an extreme display of empathetic connection to her subject, and later, when the ghostly image of the survivor is projected over the artist’s own face, there is almost a collapse between artist and subject. However, the artist stops short of appropriating the survivor’s testimony, closing her mouth as he recounts the violent death of his family. While this work questions the limits of empathy cultivated through posttraumatic testimony, it also brings up a disturbing dimension of postmemory: “if we adopt the transformative or traumatic experiences of others as ones we might ourselves have lived through… can we do so without imitating or over-identifying with them?” Hirsch asks. Your Voice Came Through My Throat seems to skirt the delicate border between empathy and appropriation, but it remains a powerful moment of intergenerational memory transfer.

Still from "Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat" (2009)

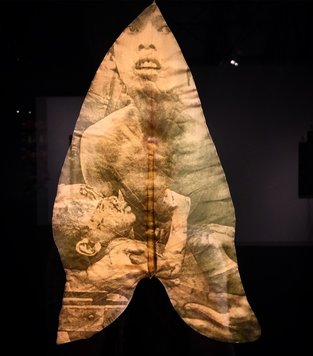

In line with new directions in memory studies, two works examine the environment as it shapes personal and collective memories of trauma. In one of the exhibition’s most striking works, Vietnamese artist Bihn Danh prints images from the Vietnam War on leaves using a photosynthetic process in a series called

"Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War" (2005-2009). Danh juxtaposes three leaves bearing images of American soldiers during combat with four leaves depicting the devastation of the war, where wounded children are held by visibly traumatized adults. By bringing together the natural, the leaves and images of familial intimacies, with the unnatural mechanisms and trauma of war, Danh asks us to confront the process of memory as both an organic and mediated process. The

diasporic biography of the artist intensifies the wartime trauma depicted on the leaves; Danh and his family left Vietnam as refugees shortly after he was born and he has been unable to imaginatively return to his homeland as it existed for his parents, before the conflict and their resulting exile. His multiple traumatic displacements are reflected in his choice of organic medium: though they are preserved in resin, eventually these delicate leaf prints will fade and completely disintegrate, demonstrating the limited longevity of postmemory.

"Holding 2" (2009)

Vandy Rattana also explores the aftermath of the Vietnam War through his photographic series,

Bomb Ponds (2009), which document the bomb craters littering the Cambodian countryside left in the aftermath of American bombing raids starting in 1969. The craters remain today, some filled with toxic water, as an enduring and inescapable environmental reminder of the war, asking us to consider how the environment continues to shape the lives and memories of multiple generations by bearing the scars of traumatic pasts.

Image from Series "Bomb Ponds" (2009)

Given the gravity of the exhibition, I originally had difficulty navigating the levity of the “future memory” section, where artists playfully stretch memory to its imaginative limits, at times abandoning the generational theme organizing the rest of the exhibit. Contrasting the traumatic landscapes of

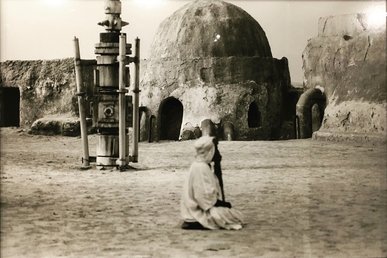

Bomb Ponds with Rä di Martino’s photographic series

Every World’s a Stage (Beggar in the Ruins of Star Wars) (2012), which features a Tunisian beggar amongst abandoned Star Wars sets, potentially trivializes the earlier photographs. While di Martino’s point is that these artificial environments take on new memories for different populations—that those who use the sets today as dwellings do so without knowledge of the pop-culture phenomenon that is Star Wars—the fictional conflict of the films pales in comparison to the environmental imprint of the war represented in

Bomb Ponds.

"Every World's a Stage" (2012)

Similarly, Mike Kelley’s installation

Kandor 17 (2007), which imagines Superman as a diasporic subject, despite its melancholic undertones, seems almost trivial compared to the actual diasporic experiences of Danh. While many of us know that Superman’s journey to Earth was precipitated by the destruction of his home planet, in a later series Krypton’s capital,

Kandor, survives, albeit in shrunken form.

Kandor 17 thus laments Superman’s inability to return to his home even as he is tasked with preserving the miniaturized city and its inhabitants under a bell jar displayed in his Fortress of Solitude. On the surface,

Kandor 17’s bright color palate and fanciful recreation of a fictional universe seems to undermine the gravity of diasporic memory presented elsewhere in the exhibit, however, when one remembers that Jewish immigrants fueled the early comic book industry, we begin to see the gravity, and yes, solitude, behind the playful exterior of Kelley’s installation.

[4] Fitting with the museum’s larger mission to present contemporary Jewish culture and the exhibition’s focus on generational memory,

Kandor 17 seemingly asks us to think about how the Jewish diaspora has been mediated and remediated throughout the past century as we interpret and reinterpret cultural touchstones like Superman.

Detail "Kandor 17" (2007)

“From Generation to Generation” will be at the Contemporary Jewish Museum until April 2, 2017.

[1] Star, Lori. “Director’s Foreword.”

From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art. Eds. Pierre-François Galpin and Lily Siegel. San Francisco: The Contemporary Jewish Museum, 2016. 1-3.

[2] Hirsch, Marianne. “Connective Arts of Postmemory.”

From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art. Eds. Pierre-François Galpin and Lily Siegel. San Francisco: The Contemporary Jewish Museum, 2016. 69-75. All citations from Hirsch in this post are taken from the exhibition catalogue, although she has defined and refined the concept of postmemory in multiple books and articles, including

Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory and

The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust.

[3] This event would become known as one of many “Bloody Sundays,” see Ann Rigney’s earlier blog post,

“Transnational Bloody Sundays: Multi-Sited Memory.”

[4] The history of which was fictionally represented by Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize winning

The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000).