In fall 2014, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign will host a cross-campus initiative marking the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I.

The Great War: Experiences, Representations, Effects will bring together faculty, students, and community members to explore the impact of the war from multiple perspectives—historical, cultural, political, and artistic. During the course of the semester-long initiative,

Days and Memory will serve as the project blog, publishing reflections and reports on issues related to the Great War. As you can see from the initiative’s website, a diverse array of activities is planned for the fall, including a team-taught history course on

“World War I and the Making of the Global Twentieth Century,” lectures by such renowned scholars as Timothy Snyder and Taner Akçam, performances of the musical

Oh, What a Lovely War!, a film series, an

exhibition of French propaganda posters, and much more.

Most of us involved in the organization of

The Great War: Experiences, Representations, Effects are not scholars of World War I. My own work has been on the representations, memories, and legacies of the Second World War and the Holocaust, but it was clear to me that such an important anniversary deserves to be marked and that its implications need to be explored. Indeed, as the historian Jay Winter argues in

Remembering War: The Great War Between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, World War I spurred the confrontation with trauma, mass violence, and memory that we now associate especially with World War II: “it is in the Great War that we can see some of the most powerful impulses and sources of the later memory boom, a set of concerns with which we still live, and—given the violent landscape of contemporary life—of which our children and grandchildren are unlikely to be free. . . . [I]t is important to recognize the extent to which in Europe and elsewhere the shadow of the Great War has been cast over later commemorative forms and cadences.”

Because of research I have been doing on Holocaust memory in contemporary Germany, I have spent the last two weeks in Berlin—perhaps the center of commemorative confrontation with National Socialism and its legacies. This year, however, reflection on World War I has taken over and can be found in different forms throughout the city. The Deutsches Historisches Museum (the German Historical Museum) has a large exhibit running called simply

Der Erste Welt Krieg, 1914-1918 (The First World War, 1914-1918).

The State Museums of Berlin are sponsoring a full program of exhibitions and conferences, and the Humboldt University has organized a series of discussions and lectures under the rubric

“The Berlin University in the First World War: What History does the University of the Present Need?” No doubt this is just the tip of the iceberg.

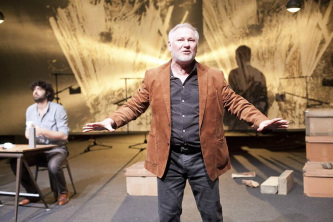

As a cultural critic, I have been especially interested in artistic confrontations with the war. The HAU Theater—one of Berlin’s most experimental venues—hosted an ambitious documentary theater production this month created by Hans-Werner Kroesinger and Regine Dura under the title

Schlachtfeld Erinnerung, 1914/2014 [Battlefield Memory, 1914/2014].

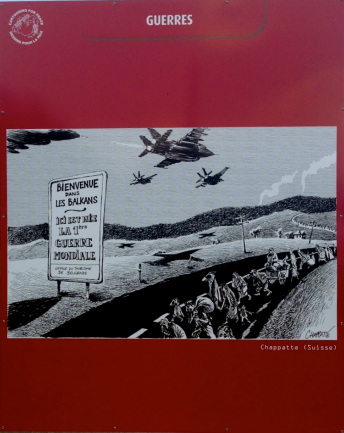

Schlachtfeld Erinnerung is a multilingual play; the four actors alternate between German, English, Bosnian, and Serbian, and frequently layer two languages on top of each other. The script draws on diverse historical, political, and literary sources to present a multi-perspectival reflection on Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as well as consideration of the prehistory and long-term legacies of conflict in the Balkans. As recent news reports have illustrated, the meaning of the assassination in Sarajevo remains a hotly contested matter bearing on contemporary politics in ex-Yugoslavia and the play provides important context for those debates.

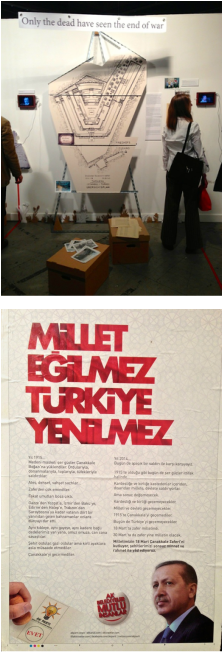

Schlachtfeld Erinnerung is also accompanied by Dura’s exhibit

Open Spaces, which was staged first in Istanbul and focuses especially on German-Turkish relations during World War I. Like the play, the exhibition is fashioned from an array of documentary materials; it assembles an archive of interviews, documents, and images that reframes understanding of relations between Germany and Turkey that are currently dominated by the aftermath of guestworker migration and conflicts over Turkey’s potential accession to the European Union. These are also very current, contested issues, and the exhibition successfully makes the case for the war’s continuing resonance in Turkey—as in this example of a recent campaign poster by the ruling AKP calling on the memory of Gallipoli in order to convince Turks of continuing threats to their sovereignty.

Schlachtfeld Erinnerung is not an entirely successful production, but even its miscues raise interesting questions for those of us reflecting on the Great War’s commemoration. One wonders, for example, about the decision to tell this story through the voices of four men. Doesn’t that confirm a long-outdated association of war solely with men’s experiences? How would the play have changed if women’s voices were also included? This surprising absence of those voices (albeit less surprising in Germany than it might be in the US) prompts reflection on how questions of gender will enter into the centenary.

Another dramaturgical choice I wondered about involves the way the play’s documentary mode leads it to privilege carefully dated events. It is filled with monologues that begin something like this: “On October 8, 1908…” While historical specificity will be important to any understanding of the war, the fetishization of the date—even if meant ironically, as may be the case here—may distract from larger underlying forces and, in any case, simply doesn’t work well as theater. The highpoints of the play were occasions in which personal stories broke through the accumulation of chronology, and humor lightened the (understandably) serious tone of the work. The insistence on the date raises questions about narrative: how can the story of the war be told in a way that coordinates the specificity of events, the singularity of experiences, and the deeper structures out of which events and experiences emerge? How can this work of coordination be done in a way that engages audiences without trivializing history?

Finally, there is the question of language and the larger issue of perspective that it opens up. Schlachtfeld Erinnerung is especially innovative, as I’ve mentioned, in insisting on the use of multiple languages. It catches audiences’ attention immediately by starting not in the language of the play’s title (German), but rather in Bosnian. Throughout the play, speeches and dialogue were usually translated, sometimes sequentially, but often simultaneously. Over the course of the almost two hour long play, this strategy became irritating, as the simultaneity of the languages meant that often neither language could be understood. There are good aesthetic and political reasons for experimenting in this way, but in insisting on the opacity of language the play also pushes once again the boundaries of reception. When we tell stories of violence and trauma—especially stories that are necessarily transnational and transcultural—how can we calibrate the balance of translatability and opacity? A performance like Schlachtfeld Erinnerung is a perfect venue for exploring this issue, but the play also demonstrates (despite itself) the difficulty of creating multi-perspectival and multilingual narrative.

It’s obvious that the issues at stake here are not unique to World War I, but the Great War provides an occasion for renewed reflection on these and many other questions. We hope that this blog can serve as one site for such reflection in the coming months. Please join us and take part in the discussion.

If you would like to follow the events associated with the

The Great War: Experiences, Representations, Effects at the University of Illinois, you can find the website

here, or join our Facebook group page

here. A calendar of upcoming events around campus can be found

here.